[Federal Register Volume 77, Number 58 (Monday, March 26, 2012)][Rules and Regulations]

[Pages 17574-17896]

From the Federal Register Online via the Government Printing Office [www.gpo.gov]

[FR Doc No: 2012-4826]

Vol. 77

Monday,

No. 58

March 26, 2012

Part II

Department of Labor

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

29 CFR 1910, 1915 and 1926

Hazard Communication; Final Rule

Federal Register / Vol. 77 , No. 58 / Monday, March 26, 2012 / Rules

and Regulations

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926

[Docket No. OSHA-H022K-2006-0062 (formerly Docket No. H022K)]

RIN 1218-AC20

Hazard Communication

AGENCY: Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), DOL.

ACTION: Final rule.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

SUMMARY: In this final rule, OSHA is modifying its Hazard Communication

Standard (HCS) to conform to the United Nations' Globally Harmonized

System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS). OSHA has

determined that the modifications will significantly reduce costs and

burdens while also improving the quality and consistency of information

provided to employers and employees regarding chemical hazards and

associated protective measures. Consistent with the requirements of

Executive Order 13563, which calls for assessment and, where

appropriate, modification and improvement of existing rules, the Agency

has concluded this improved information will enhance the effectiveness

of the HCS in ensuring that employees are apprised of the chemical

hazards to which they may be exposed, and in reducing the incidence of

chemical-related occupational illnesses and injuries.

The modifications to the standard include revised criteria for

classification of chemical hazards; revised labeling provisions that

include requirements for use of standardized signal words, pictograms,

hazard statements, and precautionary statements; a specified format for

safety data sheets; and related revisions to definitions of terms used

in the standard, and requirements for employee training on labels and

safety data sheets. OSHA is also modifying provisions of other

standards, including standards for flammable and combustible liquids,

process safety management, and most substance-specific health

standards, to ensure consistency with the modified HCS requirements.

The consequences of these modifications will be to improve safety, to

facilitate global harmonization of standards, and to produce hundreds

of millions of dollars in annual savings.

DATES: This final rule becomes effective on May 25, 2012 Affected

parties do not need to comply with the information collection

requirements in the final rule until the Department of Labor publishes

in the Federal Register the control numbers assigned by the Office of

Management and Budget (OMB). Publication of the control numbers

notifies the public that OMB has approved these information collection

requirements under the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995.

The incorporation by reference of the specific publications listed

in this final rule is approved by the Director of the Federal Register

as of May 25, 2012.

ADDRESSES: In compliance with 28 U.S.C. 2112(a), the Agency designates

Joseph M. Woodward, Associate Solicitor for Occupational Safety and

Health, Office of the Solicitor, Room S-4004, U.S. Department of Labor;

200 Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20210, as the recipient of

petitions for review of this final standard.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: For general information and press

inquiries, contact: Frank Meilinger, OSHA Office of Communications,

Room N-3647, U.S. Department of Labor, 200 Constitution Avenue NW.,

Washington, DC 20210, telephone (202) 693-1999. For technical

information, contact: Dorothy Dougherty, Director, Directorate of

Standards and Guidance, Room N-3718, OSHA, U.S. Department of Labor,

200 Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20210; telephone (202) 693-

1950.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: This final rule modifies the Hazard

Communication standard (HCS) and aligns it with the Globally Harmonized

System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) as

established by the United Nations (UN). This action is consistent with

Executive Order 13563 and, in particular, with its requirement of

"retrospective analysis of rules that may be outmoded, ineffective,

insufficient, or excessively burdensome." The preamble to the final

rule provides a synopsis of the events leading up to the establishment

of the final rule, a detailed description of OSHA's rationale for the

necessity of the modification, and final economic and voluntary

flexibility analyses that support the Agency's determinations. Also

included are explanations of the specific provisions that are modified

in the HCS and other affected OSHA standards and OSHA's responses to

comments, testimony, and data submitted during the rulemaking. The

discussion follows this outline:

I. Introduction

II. Events Leading to the Revised Hazard Communication Standard

III. Overview of the Final Rule and Alternatives Considered

IV. Need and Support for the Revised Hazard Communication Standard

V. Pertinent Legal Authority

VI. Final Economic Analysis and Voluntary Regulatory Flexibility

Analysis

VII. OMB Review Under the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995

VIII. Federalism and Consultation and Coordination With Indian

Tribal Governments

IX. State Plans

X. Unfunded Mandates

XI. Protecting Children From Environmental Health and Safety Risks

XII. Environmental Impacts

XIII. Summary and Explanation of the Modifications to the Hazard

Communication Standard

(a) Purpose

(b) Scope

(c) Definitions

(d) Hazard Classification

(e) Written Hazard Communication Program

(f) Labels and Other Forms of Warning

(g) Safety Data Sheets

(h) Employee Information and Training

(i) Trade Secrets

(j) Effective Dates

(k) Other Standards Affected

(l) Appendices

XIV. Authority and Signature

The HCS requires that chemical manufacturers and importers evaluate

the chemicals they produce or import and provide hazard information to

downstream employers and employees by putting labels on containers and

preparing safety data sheets. This final rule modifies the current HCS

to align with the provisions of the UN's GHS. The modifications to the

HCS will significantly reduce burdens and costs, and also improve the

quality and consistency of information provided to employers and

employees regarding chemical hazards by providing harmonized criteria

for classifying and labeling hazardous chemicals and for preparing

safety data sheets for these chemicals.

OSHA is required by the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act of

1970 to assure, as far as possible, safe and healthful working

conditions for all working men and women. Section 3(8) of the OSH Act

(29 U.S.C. 652(8)) empowers the Secretary of Labor to promulgate

standards that are "reasonably necessary or appropriate to provide

safe or healthful employment and places of employment." This language

has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to require that an OSHA

standard address a significant risk and reduce this risk significantly.

See Industrial Union Dep't v. American Petroleum Institute, 448 U.S.

607 (1980). As discussed in Sections IV and V of this preamble, OSHA

finds that inadequate communication to employees regarding the hazards

of chemicals constitutes a significant

risk of harm and estimates that the final rule will reduce this risk

significantly.

Section 6(b)(7) of the Act (29 U.S.C. 655(b)(7)) allows OSHA to

make appropriate modifications to its hazard communication requirements

as new knowledge and techniques are developed. The GHS system is a new

approach that has been developed through international negotiations and

embodies the knowledge gained in the field of chemical hazard

communication since the current rule was first adopted in 1983. As

indicated in Section IV of this preamble, OSHA finds that modifying the

HCS to align with the GHS will enhance worker protections

significantly. As noted in Section VI of this preamble, these

modifications to HCS will also result in less expensive chemical hazard

management and communication. In this way, the modifications are in

line with the requirements of Executive Order 13563 and its call for

streamlining of regulatory burdens.

OSHA is also required to determine if its standards are

technologically and economically feasible. As discussed in Section VI

of this preamble, OSHA has determined that this final standard is

technologically and economically feasible.

The Regulatory Flexibility Act, as amended by the Small Business

Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA), requires OSHA to

determine if a regulation will have a significant impact on a

substantial number of small entities. As discussed in Section VI, OSHA

has determined and certified that this rule will not have a significant

impact on a substantial number of small entities.

Executive Orders 13563 and 12866 require OSHA to assess the

benefits and costs of final rules and of available regulatory

alternatives. Executive Order 13563 emphasizes the importance of

quantifying both costs and benefits, reducing costs, harmonizing rules,

and promoting flexibility. This rule has been designated an

economically significant regulatory action under section 3(f)(1) of

Executive Order 12866. Accordingly, the rule has been reviewed by the

Office of Management and Budget, and the remainder of this section

summarizes the key findings of the analysis with respect to the costs

and benefits of the final rule.

Because this final rule modifies the current HCS to align with the

provisions of the UN's GHS, the available alternatives to the final

rule are somewhat limited. The Agency has qualitatively discussed the

two major alternatives to the proposed rule--(1) voluntary adoption of

GHS within the existing HCS framework and (2) a limited adoption of

specific GHS components--in Section III of this preamble, but

quantitative estimates of the costs and benefits of these alternatives

could not reasonably be developed. However, OSHA has determined that

both of these alternatives would eliminate significant portions of the

benefits of the rule, which can only be achieved if the system used in

the U.S. is consistently and uniformly applied throughout the nation

and in conformance with the internationally harmonized system.

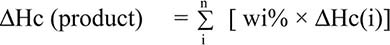

Table SI-1, derived from material presented in Section VI of this

preamble, provides a summary of the costs and benefits of the final

rule. As shown, the final rule is estimated to prevent 43 fatalities

and 521 injuries and illnesses annually. Also as shown, OSHA estimates

that the monetized health and safety benefits of the final rule are

$250 million annually and that the annualized cost reductions and

productivity gains are $507 million annually. In addition, OSHA

anticipates that the final rule will generate substantial (but

unquantified) savings from simplified hazard communication training and

from expanded opportunities for international trade due to a reduction

in trade barriers.

The estimated cost of the rule is $201 million annually. As shown

in Table SI-1, the major cost elements associated with the final rule

include the classification of chemical hazards in accordance with the

GHS criteria and the corresponding revision of safety data sheets and

labels to meet new format and content requirements ($22.5 million);

training for employees to become familiar with new warning symbols and

the revised safety data sheet format ($95.4 million); management

familiarization and other management-related costs as may be necessary

($59.0 million); and costs to purchase upgraded label printing

equipment and supplies or to purchase pre-printed color labels in order

to include the hazard warning pictogram enclosed in a red-bordered

diamond on the product label ($24.1 million).

The final rule is estimated to generate net monetized benefits of

$556 million annually, using a discount rate of 7 percent to annualize

costs and benefits. Using a 3 percent discount rate instead would have

the effect of lowering the costs to $161 million per year and

increasing the gross benefits to $839 million per year. The result

would be to increase net benefits from $556 million to $678 million per

year.

These estimates are for informational purposes only and have not

been used by OSHA as the basis for its decision concerning the

requirements for this final rule.

BILLING CODE 4510-26-P

[GRAPHIC] [TIFF OMITTED] TR26MR12.000

BILLING CODE 4510-26-C

I. Introduction

In the preamble, OSHA refers to supporting materials. References to

these materials are given as "Document ID " followed by the

last four digits of the document number. The referenced materials are

posted in Docket No. OSHA-H022K-2006-0062, which is available at http://www.regulations.osha.gov;

however, some information (e.g., copyrighted

material) is not publicly available to read or download through that

Web site. All of the documents are available for inspection and, where

permissible, copying at the OSHA Docket Office, U.S. Department of

Labor, Room N-2625, 200 Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20210.

II. Events Leading to the Revised Hazard Communication Standard

The HCS was first promulgated in 1983 and covered the manufacturing

sector of industry (48 FR 53280, Nov. 25, 1983). (Please note: The

Agency's HCS (29 CFR 1910.1200; 1915.1200; 1917.28; 1918.90; and

1926.59) will be referred to as the "current HCS" throughout this

rule.) In 1987, the Agency expanded the scope of coverage to all

industries where employees are potentially exposed to hazardous

chemicals (52 FR 31852, Aug. 24, 1987). Although full implementation in

the non-manufacturing sector was delayed by various court and

administrative actions, the rule has been fully enforced in all

industries regulated by OSHA since March 17, 1989 (54 FR 6886, Feb. 15,

1989) (29 CFR 1910.1200; 1915.1200; 1917.28; 1918.90; and 1926.59). In

1994, OSHA made minor changes and technical amendments to the HCS to

help ensure full compliance and achieve better protection of employees

(59 FR 6126, Feb. 9, 1994). The development of the HCS is discussed in

detail in the preambles to the original and revised final rules (See 48

FR at 53280-53281; 52 FR at 31852-31854; and 59 FR at 6127-6131). This

discussion will focus on the sequence of events leading to the

development of the GHS and the associated modifications to the HCS

included in the final rule.

The current HCS requires chemical manufacturers and importers to

evaluate the chemicals they produce or import to determine if they are

hazardous. The standard provides definitions of health and physical

hazards to use as the criteria for determining hazards in the

evaluation process. Information about hazards and protective measures

is then required to be conveyed to downstream employers and employees

through labels on containers and through material safety data sheets,

which are now called "safety data sheets" (SDS) under the final rule

and in this preamble. All employers with hazardous chemicals in their

workplaces are required to have a hazard communication program,

including container labels, safety data sheets, and employee training.

Generally, under the final rule, these obligations on manufacturers,

importers, and employers remain, but how hazard communication is to be

accomplished has been modified.

To protect employees and members of the public who are potentially

exposed to hazardous chemicals during their production, transportation,

use, and disposal, a number of countries have developed laws that

require information about those chemicals to be prepared and

transmitted to affected parties. The laws vary on the scope of

chemicals covered, definitions of hazards, the specificity of

requirements (e.g., specification of a format for safety data sheets),

and the use of symbols and pictograms. The inconsistencies among the

laws are substantial enough that different labels and safety data

sheets must often be developed for the same product when it is marketed

in different nations.

Within the U.S., several regulatory authorities exercise

jurisdiction over chemical hazard communication. In addition to OSHA,

the Department of Transportation (DOT) regulates chemicals in

transport; the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) regulates

consumer products; and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

regulates pesticides, as well as exercising other authority over the

labeling of chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Each of

these regulatory authorities operates under different statutory

mandates, and all have adopted distinct hazard communication

requirements.

Tracking and complying with the hazard communication requirements

of different regulatory authorities is a burden for manufacturers,

importers, distributors, and transporters engaged in commerce in the

domestic arena. This burden is magnified by the need to develop

multiple sets of labels and safety data sheets for each product in

international trade. Small businesses have particular difficulty in

coping with the complexities and costs involved. The problems

associated with differing national and international requirements were

recognized and discussed when the HCS was first promulgated in 1983. At

that time, OSHA committed to periodically reviewing the standard in

recognition of an interagency trade policy that supported the U.S.

pursuing international harmonization of requirements for chemical

classification and labeling. The potential benefits of harmonization

were noted in the preamble of the 1983 standard:

* * * [O]SHA acknowledges the long-term benefit of maximum

recognition of hazard warnings, especially in the case of containers

leaving the workplace which go into interstate and international

commerce. The development of internationally agreed standards would

make possible the broadest recognition of the identified hazards

while avoiding the creation of technical barriers to trade and

reducing the costs of dissemination of hazard information by

elimination of duplicative requirements which could otherwise apply

to a chemical in commerce. As noted previously, these regulations

will be reviewed on a regular basis with regard to similar

requirements which may be evolving in the United States and in

foreign countries. (48 FR at 53287)

OSHA has actively participated in many such efforts in the years

since that commitment was made, including trade-related discussions on

the need for harmonization with major U.S. trading partners. The Agency

issued a Request for Information (RFI) in the Federal Register in

January 1990, to obtain input regarding international harmonization

efforts, and on work being done at that time by the International

Labour Organization (ILO) to develop a convention and recommendations

on safety in the use of chemicals at work (55 FR 2166, Jan. 22, 1990).

On a closely related matter, OSHA published a second RFI in May 1990,

requesting comments and information on improving the effectiveness of

information transmitted under the HCS (55 FR 20580, May 17, 1990).

Possible development of a standardized format or order of information

was raised as an issue in the RFI. Nearly 600 comments were received in

response to this request. The majority of responses expressed support

for a standard safety data sheet format, and the majority of responses

that expressed an opinion on the topic favored a standardized format

for labels as well.

In June 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and

Development issued a mandate (Chapter 19 of Agenda 21), supported by

the U.S., calling for development of a globally harmonized chemical

classification and labeling system:

A globally harmonized hazard classification and compatible

labeling system, including material safety data sheets and easily

understandable symbols, should be available, if feasible, by the

year 2000.

This international mandate initiated a substantial effort to develop

the GHS, involving numerous international organizations, many countries, and

extensive stakeholder representation.

A coordinating group comprised of countries, stakeholder

representatives, and international organizations was established to

manage the work. This group, the Inter-Organization Programme for the

Sound Management of Chemicals Coordinating Group for the Harmonization

of Chemical Classification Systems, established overall policy for the

work and assigned tasks to other organizations. The Coordinating Group

then took the work of these organizations and integrated it to form the

GHS. OSHA served as chair of the Coordinating Group.

The work was divided into three main parts: classification criteria

for physical hazards; classification criteria for health and

environmental hazards (including criteria for mixtures); and hazard

communication elements, including requirements for labels and safety

data sheets. The criteria for physical hazards were developed by a

United Nations Sub-committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous

Goods/International Labour Organization working group and were based on

the already harmonized criteria for the transport sector. The criteria

for classification of health and environmental hazards were developed

under the auspices of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development. The ILO developed the hazard communication elements. OSHA

participated in all of this work, and served as U.S. lead on

classification of mixtures and hazard communication.

Four major existing systems served as the primary basis for

development of the GHS. These systems were the requirements in the U.S.

for the workplace, consumers, and pesticides; the requirements of

Canada for the workplace, consumers, and pesticides; European Union

directives for classification and labeling of substances and

preparations; and the United Nations Recommendations on the Transport

of Dangerous Goods. The requirements of other systems were also

examined as appropriate, and taken into account as the GHS was

developed. The primary approach to reconciling these systems involved

identifying the relevant provisions in each system; developing

background documents that compared, contrasted, and explained the

rationale for the provisions; and undertaking negotiations to find an

agreed approach that addressed the needs of the countries and

stakeholders involved. Principles to guide the work were established,

including an agreement that protections of the existing systems would

not be reduced as a result of harmonization. Thus, countries could be

assured that the existing protections of their systems would be

maintained or enhanced in the GHS.

An interagency committee under the auspices of the Department of

State coordinated U.S. involvement in the development of the GHS. In

addition to OSHA, DOT, CPSC, and EPA, other agencies were involved that

had interests related to trade or other aspects of the GHS process.

Different agencies took the lead in various parts of the discussions.

Positions for the U.S. in these negotiations were coordinated through

the interagency committee. Interested stakeholders were kept informed

through email dissemination of information, as well as periodic public

meetings. In addition, the Department of State published a notice in

the Federal Register that described the harmonization activities, the

agencies involved, the principles of harmonization, and other

information, as well as invited public comment on these issues (62 FR

15951, Apr. 3, 1997). Stakeholders also actively participated in the

discussions at the international level and were able to present their

views directly in the negotiating process. The GHS was formally adopted

by the new United Nations Committee of Experts on the Transport of

Dangerous Goods and the Globally Harmonized System of Classification

and Labelling of Chemicals in December 2002. In 2003, the adoption was

endorsed by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.

Countries were encouraged to implement the GHS as soon as possible, and

have fully operational systems by 2008. This goal was adopted by

countries in the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, and was

endorsed by the World Summit on Sustainable Development. The U.S.

participated in these groups, and agreed to work toward achieving these

goals.

OSHA published an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) on

the GHS in September of 2006 (71 FR 53617, Sept. 12, 2006). At the same

time the ANPR was published, OSHA made available on its Web site a

document summarizing the GHS (http://www.osha.gov). The ANPR provided

information about the GHS and its potential impact on the HCS, and

sought input from the public on issues related to GHS implementation.

Over 100 responses were received, and the comments and information

provided were taken into account in the development of the

modifications to the HCS included in the September 2009 Notice of

Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) (74 FR 50279-50549, Sept. 30, 2009). A

notice of correction was published on November 5, 2009, in order to

correct misprints in the proposal (74 FR 57278, Nov. 5, 2009). Over 100

comments were received in response to the NPRM. Commenters represented

the broad spectrum of affected parties and included government

agencies, industries, professional and trade associations, academics,

employee organizations and individuals. Public hearings were held in

Washington, DC, from March 2 through March 5, 2010, and in Pittsburgh,

PA, on March 31, 2010. Over 40 panels participated in the hearings. The

comments, testimony, and other data received regarding this rulemaking

were overwhelmingly favorable, and will be discussed in detail later in

this preamble. The final post-hearing comment period for further

submissions and briefs ended and the record was certified by

Administrative Law Judge Stephen L. Purcell and closed on May 31, 2010.

Executive Order 13563, emphasizing the importance of retrospective

analysis of rules, was issued on January 18, 2011.

This final rule is based on Revision 3 of the GHS. The adoption of

the GHS will improve OSHA's current HCS standard by providing

consistent, standardized hazard communication to downstream users.

However, even after the U.S. and other countries implement the GHS, it

will continue to be updated in the future. These updates to the GHS

will be completed as necessary to reflect new technological and

scientific developments as well as provide additional explanatory text.

Any future changes to the HCS to adopt subsequent changes to the GHS

would require OSHA's rulemaking procedures.

OSHA will remain engaged in activities related to the GHS. The U.S.

is a member of the United Nations Committee of Experts on the Transport

of Dangerous Goods and the Globally Harmonized System of Classification

and Labelling of Chemicals, as well as the Sub-committee of Experts on

the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of

Chemicals, where OSHA is currently the Head of the U.S. Delegation.

These permanent UN bodies have international responsibility for

maintaining, updating as necessary, and overseeing the implementation

of the GHS. OSHA and other affected Federal agencies actively

participate in these UN groups. In addition, OSHA will also continue to

participate in the GHS Programme Advisory Group under the United

Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). UNITAR is

responsible for helping countries implement the GHS, and has ongoing

programs to prepare guidance documents, conduct regional workshops, and

implement pilot projects in a number of nations. OSHA will also

continue its involvement in interagency discussions related to

coordination of domestic implementation of the GHS, and in discussions

related to international work to implement and maintain the GHS.

III. Overview of the Final Rule and Alternatives Considered

Based on consideration of the record as a whole, OSHA has modified

the HCS to make it consistent with the GHS. OSHA finds that harmonizing

the HCS with the GHS will improve worker understanding of the hazardous

chemicals they encounter every day. Such harmonization will also reduce

costs for employers.

OSHA believes that adopting the GHS will result in a clearer, more

effective methodology for conveying information on hazardous chemicals

to employers and employees. Commenters overwhelmingly supported the

revision, and their submissions form a strong evidentiary basis for

this final rule. The American Health Care Association stated that the

GHS "would enhance the effectiveness of the HCS in ensuring that

employees are apprised of the chemical hazards to which they might be

exposed" (Document ID 0346). The National Institute of

Environmental Health Sciences concurred, and added that adopting the

GHS "would provide better worker health and safety protections"

(Document ID 0347). (See also Document ID 0303, 0313,

0322, 0324, 0327, 0328, 0329, 0330, 0331, 0334, 0335, 0336, 0339, 0340,

0341, 0344, 0345, 0346, 0347, 0349, 0350, 0351, 0352, 0353, 0354, 0356,

0357, 0359, 0363, 0365, 0367, 0369, 0370, 0371, 0372, 0374, 0375, 0376,

0377, 0378, 0379, 0381, 0382, 0383, 0385, 0386, 0387, 0388, 0389, 0390,

0392, 0393, 0396, 0397, 0399, 0400, 0402, 0403, 0404, 0405, 0407, 0408,

0409, 0410, 0411, 0412, 0414, 0417, 0453, 0456, 0461, and 0463.)

Consistent with Executive Order 13563, OSHA has concluded that the

revision significantly improves the current HCS standard. Moreover,

there is widespread agreement that aligning the HCS with the GHS would

establish a valuable, systematic approach for employers to evaluate

workplace hazards, and provide employees with consistent information

regarding the hazards they encounter. A member of the United Steel

Workers aptly summed up the revision by stating that "the HCS in 1983

gave the workers the 'right to know' but the GHS will give the workers

the 'right to understand' " (Document ID 0403). The American

Society of Safety Engineers (ASSE) concurred, stating that adoption of

the HCS was "necessary to help this nation's workers deal with the

increasingly difficult challenge of understanding the hazards and

precautions needed to handle and use chemicals safely in an

increasingly connected workplace" (Document ID 0336).

Phlymar, ORC, BCI, 3M, American Iron & Steel Institute, and the North

American Metals Council (NAMC) all agreed that the adoption of the GHS

would improve the quality and consistency of information and the

effectiveness of hazard communication (Documents ID 0322,

0336, 0339, 0370, 0377, 0390, 0405, and 0408). (See also Document ID

0327, 0338, 0339, 0346, 0347, 0349, 0351, 0354, 0363, 0365,

0370, 0372, 0374, 0379, 0389, 0390, 0397, 0405, 0408, and 0414.) The

evidence supporting the Agency's conclusions is discussed more

thoroughly below in Sections IV, V, and VI; the revisions to the HCS

are discussed in detail in Section XIII.

This section of the preamble provides an overview of the current

HCS and how the adoption of the GHS will change this standard.

Moreover, this section will also discuss the alternatives to mandatory

implementation and the benefits of the final rule. The specific issues

for which OSHA solicited comments in the NPRM will be discussed within

their respective sections.

1. The Hazard Communication Standard

The HCS requires a comprehensive hazard evaluation and

communication process, aimed at ensuring that the hazards of all

chemicals are evaluated, and also requires that the information

concerning chemical hazards and necessary protective measures is

properly transmitted to employees. The HCS achieves this goal by

requiring chemical manufacturers and importers to review available

scientific evidence concerning the physical and health hazards of the

chemicals they produce or import to determine if they are hazardous.

For every chemical found to be hazardous, the chemical manufacturer or

importer must develop a container label and an SDS, and provide both

documents to downstream users of the chemical. All employers with

employees exposed to hazardous chemicals must develop a hazard

communication program, and ensure that exposed employees are provided

with labels, access to SDSs, and training on the hazardous chemicals in

their workplace.

There are three information communication components in this

system--labels, SDSs, and employee training, all of which are essential

to the effective functioning of the program. Labels provide a brief,

but immediate and conspicuous, summary of hazard information at the

site where the chemical is used. SDSs provide detailed technical

information and serve as a reference source for exposed employees,

industrial hygienists, safety professionals, emergency responders,

health care professionals, and other interested parties. Training is

designed to ensure that employees understand the chemical hazards in

their workplace and are aware of protective measures to follow. Labels,

SDSs, and training are complementary parts of a comprehensive hazard

communication program--each element reinforces the knowledge necessary

for effective protection of employees. Information required by the HCS

reduces the incidence of chemical-related illnesses and injuries by

enabling employers and employees to implement protective measures in

the workplace. Employers can select less hazardous chemical

alternatives and ensure that appropriate engineering controls, work

practices, and personal protective equipment are in place. Improved

understanding of chemical hazards by supervisory personnel results in

safer handling of hazardous substances, as well as proper storage and

housekeeping measures.

Employees provided with information and training on chemical

hazards are able to fully participate in the protective measures

instituted in their workplaces. Knowledgeable employees can take the

steps required to work safely with chemicals, and are able to determine

what actions are necessary if an emergency occurs. Information on

chronic effects of exposure to hazardous chemicals helps employees

recognize signs and symptoms of chronic disease and seek early

treatment. Information provided under the HCS also enables health and

safety professionals to provide better services to exposed employees.

Medical surveillance, exposure monitoring, and other services are

enhanced by the ready availability of health and safety information.

The modifications that make up this final rule build on these core

principles by establishing a more detailed and consistent

classification system and requiring uniform labels and SDSs, which will

better ensure that workers are informed and adequately protected from

chemical exposures.

2. Current HCS Provisions for Classification, Labeling, and SDSs

The current HCS covers a broad range of health and physical

hazards. The standard is performance-oriented, providing definitions of

hazards and parameters for evaluating the evidence to determine whether

a chemical is considered hazardous. The evaluation is based upon

evidence that is currently available, and no testing of chemicals is

required.

The current standard covers every type of health effect that may

occur, including both acute and chronic effects. Definitions of a

number of adverse health effects are provided in the standard. These

definitions are indicative of the wide range of coverage, but are not

exclusive. Mandatory Appendix A of the current standard lists criteria

for specific health effects; however, it also notes that these criteria

are not intended to be an exclusive categorization scheme, but rather

any available scientific data on the chemical must be evaluated to

determine whether the chemical presents a health hazard. Any adverse

health effect that is substantiated by a study conducted according to

established scientific principles, and reporting a statistically

significant outcome, is sufficient for determining that a chemical is

hazardous under the rule.

Most chemicals in commerce are not present in the pure state (i.e.,

as individual elements or compounds), but are ingredients in mixtures

of chemicals. Evaluation of the health hazards of mixtures is based on

data for the mixture as a whole when such data are available. When data

on the mixture as a whole are not available, the mixture is considered

to present the same health hazards as any ingredients present at a

concentration of 1% or greater, or, in the case of carcinogens,

concentrations of 0.1% or greater. The current HCS also recognizes that

risk may remain at concentrations below these cut-offs, and where there

is evidence that that is the case, the mixtures are considered

hazardous under the standard.

The current HCS establishes requirements for minimum information

that must be included on labels and SDSs, but does not provide specific

language to convey the information or a format in which to provide it.

When the current HCS was issued in 1983, the public record strongly

supported this performance-oriented approach (See 48 FR at 53300-

53310). Many chemical manufacturers and importers were already

providing information voluntarily, and in the absence of specific

requirements had developed their own formats and approaches. The record

indicated that a performance-oriented approach would reduce the need

for chemical manufacturers and importers to revise these existing

documents to comply with the HCS, thus reducing the cost impact of the

standard.

3. GHS Provisions for Classification, Labeling, and SDSs

The GHS is an internationally harmonized system for classifying

chemical hazards and developing labels and safety data sheets. However,

the GHS is not a model standard that can be adopted verbatim. Rather,

it is a set of criteria and provisions that regulatory authorities can

incorporate into existing systems, or use to develop new systems.

The GHS allows a regulatory authority to choose the provisions that

are appropriate to its sphere of regulation. This is referred to as the

"building block approach." The GHS includes all of the regulatory

components, or building blocks, that might be needed for classification

and labeling requirements for chemicals in the workplace, transport,

pesticides, and consumer products. This rule only adopts those sections

of the GHS that are appropriate to OSHA's regulatory sector. For

example, while the GHS includes criteria on classifying chemicals for

aquatic toxicity, these provisions were not adopted because OSHA does

not have the regulatory authority to address environmental concerns.

The building block approach also gives regulatory agencies the

authority to select which classification criteria and provisions to

adopt. OSHA is adopting the classification criteria and provisions for

labels and SDSs, because the current HCS covers these elements. Broad

criteria were established for the GHS in order to allow regulatory

bodies to apply the same standards to a wide array of hazards. The

building block approach may also be applied to the criteria for

defining hazard categories. As a result, the GHS criteria are more

comprehensive than what was in the current HCS, and OSHA did not need

to incorporate all of the GHS hazard categories into this final rule.

Under the GHS, each hazard or endpoint (e.g., Explosives,

Carcinogenicity) is considered to be a hazard class. The classes are

generally sub-divided into categories of hazard. For example,

Carcinogenicity has two hazard categories. Category one is for known or

presumed human carcinogens while category two encompasses suspected

human carcinogens. The definitions of hazards are specific and

detailed. For example, under the current HCS, a chemical is either an

explosive or it is not. The GHS has seven categories of explosives, and

assignment to these categories is based on the classification criteria

provided. In order to determine which hazard class a mixture falls

under, the GHS generally applies a tiered approach. When evaluating

mixtures, the first step is consideration of data on the mixture as a

whole. The second step allows the use of "bridging principles" to

estimate the hazards of the mixture based on information about its

components. The third step of the tiered approach involves use of cut-

off values based on the composition of the mixture or, for acute

toxicity, a formula that is used for classification. The approach is

generally consistent with the requirements of the pre-modified HCS, but

provides more detail and specification and allows for extrapolation of

data available on the components of a mixture to a greater extent--

particularly for acute effects.

Hazard communication requirements under the GHS are directly linked

to the hazard classification. For each class and category of hazard, a

harmonized signal word (e.g., Danger), pictogram (e.g., skull and

crossbones), and hazard statement (e.g., Fatal if Swallowed) must be

specified. These specified elements are referred to as the core

information for a chemical. Thus, once a chemical is classified, the

GHS provides the specific core information to convey to users of that

chemical. The core information allocated to each category generally

reflects the degree or severity of the hazard.

Precautionary statements are also required on GHS labels. The GHS

provides precautionary statements; while they have been codified

(numbered), they are not yet considered formally harmonized. In other

words, regulatory authorities may choose to use different language for

the precautionary statements and still be considered to be harmonized

with the GHS. The GHS has codified these statements (i.e., assigned

numbers to them) as well as aligned them with the hazard classes and

categories. Codification allows the precautionary statements to be

referenced in a shorthand form and makes it easier for authorities

using them in regulatory text to organize them. In addition, there are

provisions to allow inclusion of supplementary information so that

chemical manufacturers can provide data in addition to the specified

core information.

The GHS establishes a standardized 16-section format for SDSs to

provide a consistent sequence for presentation of information to SDS

users. Items of primary interest to exposed employees and emergency responders are

presented at the beginning of the document, while more technical

information is presented in later sections. Headings for the sections

(e.g., First-aid measures, Handling and storage) are standardized to

facilitate locating information of interest. The harmonized data sheets

are consistent with the order of information included in the voluntary

industry consensus standard for safety data sheets (ANSI Z400.1).

4. Revisions to the Hazard Communication Standard

The GHS uses an integrated, comprehensive process of identifying

and communicating hazards, and the GHS modifications improve the HCS by

providing more extensive criteria for defining the hazards in a

consistent manner, as well as standardizing label elements and SDS

formats to help to ensure that the information is conveyed

consistently. The GHS does not include requirements for a written

hazard communication program, and this final rule does not make

substantive changes to the current HCS requirements for a written

hazard communication program. Nor does the GHS impose employee training

requirements; however, OSHA believes that additional training will be

necessary to ensure that employees understand the new elements,

particularly on the new pictograms. Therefore, modified training

requirements have been included in the final rule in order to address

the new label elements and SDS format required under this revised

standard.

a. Modifications

The revised HCS primarily affects manufacturers and importers of

hazardous chemicals. Pursuant to the final rule, chemical manufacturers

and importers are required to re-evaluate chemicals according to the

new criteria in order to ensure the chemicals are classified

appropriately. For health hazards, this will involve assigning the

chemical both to the appropriate hazard category and subcategory

(called hazard class). For physical hazards, these new criteria are

generally consistent with current DOT requirements for transport.

Therefore, if the chemicals are transported (i.e., they are not

produced and used in the same workplace), this classification should

already be done to comply with DOT's transport requirements. This will

minimize the work required for classifying physical hazards under the

revised rule.

Preparation and distribution of modified labels and safety data

sheets by chemical manufacturers and importers will also be required.

However, those chemical manufacturers and importers following the ANSI

Z400.1 standard for safety data sheets should already have the

appropriate format, and will only be required to make some small

modifications to the content of the sheets to be in compliance with the

final rule.

Using the revised criteria, a chemical will be classified based on

the type, the degree, and the severity of the hazard it poses. This

information will help employers and employees understand chemical

hazards and identify and implement protective measures. The detailed

criteria for classification will result in greater accuracy in hazard

classification and more consistency among classifiers. Uniformity will

be a key benefit; by following the detailed criteria, classifiers are

less likely to reach different interpretations of the same data.

b. Specific Changes From the Proposal

Based on comments from the rulemaking effort, OSHA has made some

modifications from the proposal to the final rule. These changes were

the result of OSHA's analysis of the comments and data received from

interested parties who submitted comments or participated in the public

hearings. The major changes are summarized below and are discussed in

the Summary and Explanation Section of this Preamble (Section XIII).

Safety Data Sheet

In the proposal, OSHA asked interested parties to comment on

whether OSHA's permissible exposure limits (PELs) should be included on

SDSs, as well as any other exposure limit used or recommended by the

chemical manufacturer, importer, or employer who prepares SDSs. After

reviewing and analyzing the comments and testimony, OSHA has decided

not to modify the HCS with regard to the American Conference of

Government Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) Threshold Limit Values (TLVs)

and so will continue to require ACGIH TLVs on SDSs. We have also

retained the classification listings of the International Agency for

Research on Cancer (IARC) and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) on

SDSs. As explained more fully in the Summary and Explanation, OSHA

finds that requiring ACGIH TLVs as well as the IARC and NTP

classification listings on the SDS will provide employers and employees

with useful information to help them assess the hazards presented by

their workplaces.

Labels

As discussed in the NPRM, the GHS gives individual countries the

option of using black, rather than red, borders around pictograms for

labels used in domestic commerce. OSHA proposed requiring red frames

for all labels, domestic and international. The final rule carries

forward this requirement. As discussed in Sections IV and XIII, studies

showed that there is substantial benefit to the use of color on the

label. The color red in particular will make the warnings on labels

more noticeable, because red borders are generally perceived to reflect

the greatest degree of hazard. Further, while commenters who objected

to this requirement cited the cost of printing in red ink as a reason

to allow domestic use of black borders, OSHA was unconvinced that the

costs involved made the provision infeasible, excessively burdensome,

or warranted the diminished protection provided by black borders. (See

Sections VI and XIII below.)

One option suggested by commenters was requiring a red label but

allowing manufacturers and importers to use preprinted labels with

multiple red frames. This would save costs because the preprinted label

stock could be used for different products requiring different

pictograms. Use of this option, however, would mean that the label for

a particular chemical might have empty red frames if the chemical did

not require as many pictograms as there were red frames on the label

stock.

As explained in Sections IV and XIII, OSHA has concluded that a red

border without a pictogram can create confusion and draw worker

attention away from the appropriate hazard warnings (See Section IV for

more detail). Additionally, OSHA is concerned that empty red borders

might be inconsistent with DOT regulations (See 49 CFR 172.401).

Therefore, while OSHA is not opposed to the use of preprinted stock,

OSHA has decided not to allow the use of blank red frames on finished

labels.

Hazard Classification

Another change to the final rule is the inclusion of the IARC and

NTP as resources for determining carcinogenicity. Commenters generally

supported this modification, and OSHA believes the inclusion of this

information will assist evaluators with the classification process.

Therefore, descriptions of both the IARC and NTP classification

criteria have been added to Appendix F, and IARC and NTP

classifications may be used to determine

whether a chemical should be classified as a carcinogen.

Unclassified Hazards

OSHA has made several modifications to clarify and specify the

definition for unclassified hazards, based on the comments provided.

Executive Order 13563 states that our regulatory system "must promote

predictability and reduce uncertainty," and these efforts at

clarification are designed to achieve that goal. OSHA included this

definition to preserve existing safeguards under requirements of the

HCS for chemical manufacturers and importers to disseminate information

on hazardous chemicals to downstream employers, and for all employers

to provide such information to potentially exposed employees. Inclusion

of the definition does not create new requirements. OSHA has made

certain changes to clarify application of the definition, and to ensure

that the relevant provisions do not create confusion or impose new

burdens.

In order to minimize confusion, OSHA has renamed unclassified

hazards, "hazards not otherwise classified." More fundamentally, and

in response to the majority of the comments on this issue, OSHA has

removed from the coverage of the general definition the hazards

identified in the NPRM as not currently classified under the GHS

criteria. These hazards are: pyrophoric gases, simple asphyxiants, and

combustible dust. As described below, OSHA has added definitions to the

final rule for pyrophoric gases and simple asphyxiants, and provided

guidance on defining combustible dust for purposes of complying with

the HCS. In addition, the Agency has also provided standardized label

elements for these hazardous effects.

Precautionary/Hazard Statements

In response to concerns by commenters that, on occasion, a

specified precautionary statement might not be appropriate, OSHA

modified mandatory Appendix C to provide some added flexibility. Where

manufacturers, importers, or responsible parties can show that a

particular statement is inappropriate for the product, that

precautionary statement may be omitted from the label. This is

discussed in more detail in section XIII below.

Other Standards Affected

Changing the HCS to conform to the GHS requires modification of

other OSHA standards. For example, modifications have been made to the

standards for Flammable and Combustible Liquids in general industry (29

CFR 1910.106) and construction (29 CFR 1926.152) to align the

requirements of the standards with the GHS hazard categories for

flammable liquids. Modifications to the Process Safety Management of

Highly Hazardous Chemicals standard (29 CFR 1910.119) will ensure that

the scope of the standard is not changed by the revisions to the HCS.

In addition, modifications have been made to most of OSHA's substance-

specific health standards, ensuring that requirements for signs and

labels and SDSs are consistent with the modified HCS.

Effective Dates

In the proposal, OSHA solicited comments regarding whether it would

be feasible for employers to train employees regarding the new labels

and SDSs within two years after publication of the final rule.

Additionally, OSHA inquired as to whether chemical manufacturers,

importers, distributors, and employers would be able to comply with all

the provisions of the final rule within three years, and whether a

phase-in period was necessary.

OSHA received many comments and heard testimony regarding the

effective dates which are discussed in detail in Section XIII below.

First, after analysis of the record, the Agency has determined that

covered employers must complete all training regarding the new label

elements and SDS format by December 1, 2013 since, as supported by

record, employees will begin seeing the new style labels considerably

earlier than the compliance date for labeling. Second, OSHA is

requiring compliance with all of the provisions for preparation of new

labels and safety data sheets by June 1, 2015. However, distributors

will have an additional six months (by December 1, 2015) to distribute

containers with manufacturers' labels in order to accommodate those

they receive very close to the compliance date. Employers will also be

given an additional year (by June 1, 2016) to update their hazard

communication programs or any other workplace signs, if applicable.

Additionally, OSHA has decided not to phase in compliance based on

whether a product is a substance or a mixture. OSHA has concluded that

adequate information is available for classifiers to use to classify

substances and mixtures. Finally, as discussed in the NPRM, employers

will be considered to be in compliance with the HCS during the

transition period as long as they are complying with either the

existing HCS (as it appears in the CFR as of October 1, 2011) or this

revised HCS. A detailed discussion regarding the effective dates is in

Section XIII.

5. Alternatives of Mandatory Implementation

In the NPRM, OSHA proposed several alternatives to mandatory

implementation of the GHS in response to concerns raised by commenters

through the ANPR (74 FR at 50289). Commenters generally supported the

concept of adopting the GHS as it was proposed. However, a few

commenters indicated that they were concerned with what they saw as the

cost burden on small businesses that are not involved in international

trade. To address these concerns, OSHA solicited comments in the NPRM

on several options proposed by the Agency regarding alternatives to

mandatory harmonization. The following is a discussion of these

alternatives; the potential impact and the response from participants

in the rulemaking regarding the relative benefit, feasibility, impact

on small business; and the impact on worker safety and health.

The first alternative OSHA proposed was to facilitate voluntary

adoption of GHS within the existing HCS framework, and give

manufacturers and importers the option to use the current HCS or the

GHS system. This option would have permitted companies to decide

whether they wanted to comply with the existing standard or with the

GHS. A variation of this alternative was also proposed that would have

adopted the GHS with an exemption allowing small chemical producers to

continue to use the HCS, even after this GHS-modified HCS is

promulgated.

The second alternative was a limited adoption of specific GHS

components. Under this approach, producers could either comply with the

GHS or a modified HCS that would retain the current HCS hazard

categories, but require standardized hazard statements, signal words,

and precautionary statements. A variation of this alternative would

have omitted mandatory precautionary statements.

Commenters almost universally objected to both of the alternatives

listed above (Document ID 0324, 0328, 0329, 0330, 0335, 0338,

0339, 0341, 0344, 0351, 0352, 0355, 0365, 0370, 0377, 0381, 0382, 0385,

0387, 0389, 0393, 0495, 0403, 0404, and 0412). American Industrial

Hygiene Association (AIHA), in a representative comment, stated that

"permitting voluntary use of some of the system * * * or exempting

certain sectors based on business size or other criteria [would] defeat

the purpose of revising this standard and of the GHS" (Document ID

0365). Additionally, the Compressed Gas Association stated they "would not support any

alternative approach as it would defeat the goal of global hazard

communication coordination" (Document ID 0324).

Many commenters argued that a dual system that permitted businesses

to opt out of complying with the GHS would undermine the key benefits

of implementation. For example, Ferro Corporation stated that "for GHS

to be effective and efficient in the U.S., implementation should be

consistent and congruent" (Document ID 0363). DuPont Company

argued "dual systems would be confusing for employers" (Document ID

0329). ORC also rejected voluntary implementation, reasoning

that "consistent requirements for all manufacturers and importers of

chemicals [are] needed to maximized efficiency in the chemical supply

chain" (Document ID 0370). Additionally, the AFL-CIO cited

consistent hazard information for workers and employers as the core

objective of this rulemaking (Document ID 0340).

The commenters who supported GHS as proposed indicated that

consistency was an essential aspect of this rule. Stericycle, Inc.,

stated that SDSs which "do not follow a consistent format would cause

issues in understanding and implementing the controls to limit exposure

and protect employee safety and health," and argued that exemptions

from GHS requirements would "shift the burden from the chemical

industry to all employers" (Document ID 0338). Additionally,

commenters did not support exempting small businesses from adopting the

GHS. Ecolab argued that "large and small businesses use each others'

products" and are inextricably linked, and they indicated that

voluntary adoption "could cause confusion about product hazards if two

identical products are labeled differently due solely to the size of

the business from which [they are] obtained" (Document ID

0351).

OSHA agrees that the first alternative is unworkable as even one

business's adoption of one of the alternatives would affect other

companies. As stated in the comments above, if small businesses do not

adopt the GHS, then large businesses or distributors will either have

to generate GHS classifications for chemicals purchased, or request

that small businesses supply data and labels using GHS classifications.

Likewise, chemical producers often provide their products to

distributors who then sell them to customers who are unknown to the

original producer. This would lead to a plethora of product labels, a

situation that is bound to make hazard communication far more

difficult.

Commenters specifically cited issues with safety as their basis for

rejecting the first proposed alternative. The AIHA (Document ID

0365) stated:

If employers and employees cannot have confidence that labels

and MSDSs provide a consistent safety message superficial

standardization will not improve safety. Safety is also seriously

compromised if different hazard communication systems are present in

the work area. Effective training is not possible if pictograms and

hazard statements are not used in a consistent manner * * *. All of

the approaches discussed will create competitive pressures that can

affect classification decisions and make good and consistent hazard

communication more difficult.

North American Metal Council argued that the alternative would penalize

workers of small business, and asserted that a "worker's right to know

about chemical hazards, should not depend on the source of a chemical

or the size of the worker's employer" (Document ID 0337).

Moreover, commenters asserted that the benefits derived from the

harmonized labeling of chemicals would be significantly diluted if

employers were not uniformly required to adopt the GHS. United Steel

Workers Union aptly reiterated that the primary benefit of adopting the

GHS is not the facilitation of international trade, but rather is the

protection of workers, which is "best accomplished through a uniform

system of classification leading to comprehensible hazard information"

(Document ID 0403). (See also Document ID 0339, 0351,

0376, 0377, 0382, and 0412.)

Several commenters supported the voluntary adoption of the GHS

(Document ID 0355, 0389, and 0502). For example,

Intercontinental Chemical Corporation supported voluntary adoption for

companies not involved in international trade (Document ID

0502). Additionally, Betco supported allowing "small

businesses that market domestically" to retain the current HCS and

suggested that "voluntary adoption would not be any less protective

for employees or create confusion" (Document ID 0389).

OSHA acknowledges that small chemical manufacturers will have some

burdens associated with the adoption of GHS. However, employees who use

products produced by small employers are entitled to the same

protections as those who use products produced by companies engaged in

international trade. The confusion created by two or more competing

systems would undermine the consistency of hazard communication

achievable by a GHS-modified HCS. Moreover, whether or not a product

will wind up in international trade may not be known to the

manufacturer or even the first distributer. A producer may provide a

chemical to another company, which then formulates it into a product

that is sold internationally. Thus, the original producer is involved

in international trade without necessarily realizing it. For these

reasons, OSHA has determined that, in order to achieve a national,

consistent standard, all businesses must be required to adhere to the

revised HCS.

OSHA concludes that the rulemaking record does not support adoption

of the first alternative. The majority of private industry, unions, and

professional organizations did not support this approach, arguing

persuasively that piecemeal adoption would undermine the benefits of

harmonization. As discussed above, while improvements to international

trade are a benefit of this rulemaking; they are not the primarily

intended benefit. OSHA believes that implementation of the GHS, without

exceptions based on industry or business size, will enhance worker

safety through providing consistent hazard communication and,

consequently, safe practices in the workplace. However, as indicated

above, OSHA does recognize that there are burdens with any change and

as discussed in Section XIII, OSHA will use the input OSHA has received

to the record to develop an outreach plan for additional guidance.

The second alternative, a halfway measure allowing businesses to

adopt some of the features of a GHS-modified HCS but not requiring

adoption of others, drew little interest or comment from the

participants. OSHA has concluded that this alternative, which would

have led to even more inconsistencies in hazard communication, is not a

viable alternative. OSHA's conclusion is supported by the overwhelming

number of commenters who spoke out against the first option and

strongly supported the proposed standard. Allowing employers to adopt,

say, only the provisions for the labels or safety data sheets will

result in inconsistent use of the standardized hazard statement, signal

word, and precautionary statement without clear direction on when they

would be required, a situation that is sure to compromise safety in the

workplace. Therefore, OSHA has concluded that implementation of the GHS

is also preferable to the second alternative.

Pursuant to its analysis of the entire rulemaking record, OSHA has

decided to adopt the GHS as proposed and is not incorporating any of

the alternatives into this final rule. The adoption of any of the

alternatives would undermine the key benefits associated with the GHS.

OSHA has concluded, as discussed in Section V, that the adoption of GHS

as proposed will strengthen and refine OSHA's hazard communication

system, leading to safer workplaces.

IV. Need and Support for the Modifications to the Hazard Communication

Standard

Chemical exposure can cause or contribute to many serious adverse

health effects such as cancer, sterility, heart disease, lung damage,

and burns. Some chemicals are also physical hazards and have the

potential to cause fires, explosions, and other dangerous incidents. It

is critically important that employees and employers are apprised of

the hazards of chemicals that are used in the workplace, as well as the

associated protective measures. This knowledge is needed to understand

the precautions necessary for safe handling and use, to recognize signs

and symptoms of adverse health effects related to exposure when they do

occur, and to identify appropriate measures to be taken in an

emergency.

OSHA established the need for disclosure of chemical hazard

information when the Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) was issued in

1983 (48 FR 53282-53284, Nov. 25, 1983). As noted in the NPRM (74 FR

50291, Sept. 30, 2009), this need continues to exist. The Agency

estimates that 880,000 hazardous chemicals are currently used in the

U.S., and over 40 million employees are now potentially exposed to

hazardous chemicals in over 5 million workplaces. During the September

29, 2009, press conference announcing the publication of the HCS NPRM,

Deputy Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health,

Jordan Barab, discussed the impact that the HCS has had on reducing

injury and illness rates. Mr. Barab stated that, since the HCS's

original promulgation in 1983, "OSHA estimates that chemically-related

acute injuries and illness [have] dropped at least 42%." Reiterating

information from OSHA's preliminary economic analysis in the NPRM, Mr.

Barab also stated:

[T]here are still workers falling ill or dying from exposure to

hazardous chemicals. OSHA estimates, based on BLS data, that more

than 50,000 workers became ill and 125 workers died due to acute

chemical exposure in 2007. These numbers are dwarfed by chronic

illnesses and fatalities that are estimated in the tens of

thousands.

OSHA believes that aligning the Hazard Communication Standard

with the provisions of the GHS will improve the effectiveness of the

standard and help to substantially improve worker safety and health.

The GHS will provide a common system for classifying chemicals

according to their health and physical hazards and it will specify

hazard communication elements for labeling and safety data sheets.

Data collected and analyzed by the Agency also reflect this

critical need to improve hazard communication. Chemical exposures

result in a substantial number of serious injuries and illnesses among

exposed employees. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that

employees suffered 55,400 illnesses that could be attributed to

chemical exposures in 2007, the latest year for which data are

available (BLS, 2008). In that same year, 17,340 chemical-source

injuries and illnesses involved days away from work (BLS, 2009).

The BLS data, however, do not indicate the full extent of the

problem, particularly with regard to illnesses. As noted in the

preamble to the HCS in 1983, BLS figures probably only reflect a small

percentage of the incidents occurring in exposed employees (48 FR

53284, Nov. 25, 1983). Many occupational illnesses are not reported

because they are not recognized as being related to workplace

exposures, are subject to long latency periods between exposure and the

manifestation of disease, and other factors (e.g., Herbert and

Landrigan, 2000, Document ID 0299; Leigh et al., 1997,

Document ID 0274; Landrigan and Markowitz, 1989, Document ID

0299).

While the current HCS serves to ensure that information concerning

chemical hazards and associated protective measures is provided to

employers and employees, the Agency has determined that the revisions

adopted in this final rule will substantially improve the quality and

consistency of the required information. OSHA believes these revisions

to the HCS, which align it with the GHS, will enhance workplace

protections significantly. Better information will enable employers and

employees to increase their recognition and knowledge of chemical

hazards and take measures that will reduce the number and severity of

chemical-related injuries and illnesses.

A key foundation underlying this belief relates to the

comprehensibility of information conveyed under the GHS. All hazard

communication systems deal with complicated scientific information

being transmitted to largely non-technical audiences. During the

development of the GHS, in order to construct the most effective hazard

communication system, information about and experiences with existing

systems were sought to help ensure that the best approaches would be

used. Ensuring the comprehensibility of the GHS was a key principle

during its development. As noted in a Federal Register notice published

by the U.S. Department of State (62 FR 15956, April 3, 1997): "A major

concern is to ensure that the requirements of the globally harmonized

system address issues related to the comprehensibility of the

information conveyed." This concern is also reflected in the

principles of harmonization that were used to guide the negotiations

and discussions during the development of the GHS. As described in

Section 1.1.1.6(g) of the GHS, the principles included the following:

"[T]he comprehension of chemical hazard information, by the target

audience, e.g., workers, consumers and the general public should be

addressed."

As was discussed in the proposal (74 FR 50291), to help in the

development of the GHS, OSHA had a review of the literature conducted

to identify studies on effective hazard communication, and made the

review and the analysis of the studies available to other participants

in the GHS process. One such study, prepared by researchers at the

University of Maryland, entitled "Hazard Communication: A Review of

the Science Underpinning the Art of Communication for Health and

Safety" (Sattler et al., 1997, Document ID 0191) has also

long been available to the public on OSHA's Hazard Communication web

page. Additionally, OSHA conducted an updated review of the literature

published since the 1997 review. This updated review examined the

literature relevant to specific hazard communication provisions of the

GHS (ERG, 2007, Document ID 0246).

Further work related to comprehensibility was conducted during the

GHS negotiations by researchers in South Africa at the University of

Cape Town--the result is an annex to the GHS on comprehensibility

testing (See GHS Annex 6, Comprehensibility Testing Methodology)

(United Nations, 2007, Document ID 0194). Such testing has

been conducted in some of the developing countries preparing to

implement the GHS, and has provided these countries with information

about which areas in the GHS will require more training in their

programs to ensure people understand the information. The primary purpose of these

activities was to ensure that the system developed was designed in such

a way that the messages would be effectively conveyed to the target

audiences, with the knowledge that the system would be implemented

internationally in different cultures with varying interests and

concerns.

Another principle that was established to guide development of the

GHS was the agreement that levels of protection offered by an existing

hazard communication system should not be reduced as a result of

harmonization. Following these principles, the best aspects of existing

systems were identified and included in a single, harmonized approach

to classification, labeling, and development of SDSs.

The GHS was developed by a large group of experts representing a

variety of perspectives. Over 200 experts provided technical input on

the project. The United Nations Sub-Committee of Experts on the GHS,

the body that formally adopted the GHS and is now responsible for its

maintenance, includes 35 member nations as well as 14 observer nations.

Authorities from these member states are able to convey the insight and

understanding acquired by regulatory authorities in different sectors,

and to relate their own experiences in implementation of hazard

communication requirements. In addition, over two dozen international

and intergovernmental organizations, trade associations, and unions are

represented, and their expertise serves to inform the member nations.

The GHS consequently represents a consensus recommendation of experts

with regard to best practices for effective chemical hazard