Fleet Safety at Abbott (A)1

Company: Abbott

April 2005

The manufacturing setting has been a highly visible area for worker safety programs, but in 2000, more worker fatalities were caused by vehicle crashes in the United States than by any other incident type (see Exhibit 1).

A typical driver in the U.S. travels 12,000 to 15,000 miles annually, and has a one in 15 chance of being involved in a vehicle collision each year.2 Most fleet drivers travel 20,000 to 25,000 miles or more each year, and thus have a greater exposure to crash risks.

In addition to the frequency, fleet vehicle crashes create the most costly worker injury claims, averaging over $21,000 per incident.3 Besides property damage, crashes result in lost productivity and/or lost revenue from missed sales calls and potential third-party liability claims from an at-fault crash. Since most companies self-insure fleet vehicles and drivers, the company bears the burden of these costs directly.

Given the frequency and severity of fleet vehicle crashes, and the high costs associated with these crashes, it is important for any organization that operates a fleet to take a proactive approach to fleet safety.

For many years, the safety program at Abbott focused on the manufacturing and development areas of the organization. In 1998, the company's Pharmaceutical Products Division (PPD) began to place additional focus on fleet vehicle safety. At that time Abbott employed 18,000 employees, of which 25 percent were sales and service representatives. Among the divisions, PPD had the largest domestic sales force, about 4,000 employees. This safety effort began with an analysis of past safety incidents in the division. Studies showed that 80 percent of employee fatalities and most of the severe employee injuries result from vehicle crashes. The company's benchmarking efforts revealed that its crash rate on a corporate level was about average for the pharmaceutical industry.

Joe, a corporate manager in PPD, has been given the task of improving fleet safety in the division. Joe wanted to decide immediately:

- Who should be targeted by a fleet safety program?

- How can they be influenced to drive safer?

In order to determine whom to target, Joe was interested in identifying some leading and trailing indicators that might support his recommendations.

After examining the incident data available, Joe decided initially to target new hires. The data supported that new hires are statistically at greater risk of a crash than tenured employees with the greatest likelihood of a crash occurring within the first 18 months on the job. Also, about 60 percent of the sales representatives are involved in a crash during their first five years on the job.

Joe hypothesized that there is an increased risk because the new hires are becoming accustomed to many new elements including a new job, territory, customers, products, policies and vehicle. Also, he believed that the additional risk may result from a new hire's eagerness to perform well, and thus they over-schedule and rush, both of which may lead to crashes.

Joe developed a one-hour new hire training program that covered the basics of driver safety that was incorporated into the standard orientation program and was taught by an internal staff member.

The program was easily implemented in the new hire orientation program and immediately showed some reduction in incident rates. However, the amount of reduction was minimal, and it quickly leveled off. Joe was then pondering what he should do next.

| Motor vehicle accidents | 31% |

| Other transportation incidents | 12.5% |

| Assaults & violent acts | 15.7% |

| Contact with objects & equipment | 17% |

| Falls | 12.4% |

| Exposure to harmful substances or environments | 8.1% |

| Fires and explosions | 3% |

Fleet Safety at Abbott (B)

In 1998, Abbott determined that there were three key areas with the potential for significant improvements in reducing their fleet safety incident rates: new hires, mid-level managers and high-risk drivers.

After the initial trial program of one hour of classroom instruction as part of new hire orientation failed to achieve the desired gains in safety, Joe's safety organization implemented an expanded program. To further improve the driving habits of the new hires, the Pharmaceutical Products Division (PPD) partnered with Advanced Driver Training Services, Inc. (ADTS), a company that has specialized in fleet safety training since 1983. The new program consisted of a half-day of classroom instruction and a half-day of behind-the-wheel training (see Exhibit 2 for a brief description of the program).

Since the full roll-out in 1999, the new hire crash rate has dropped significantly (see Exhibit 3). Over the three-year period from 1999 through 2001, over 2,000 new sales representatives were trained. During the year following their participation in training, the group's crash rate was approximately 50 percent lower than the rate for tenured drivers who did not attend the training. The fact that the crash rate historically had been higher for new hires than tenured drivers made these results even more significant. Incorporating the training as part of the existing new hire orientation helped contain some of the costs, plus the employees received the training before they received a company vehicle.

The second area targeted was mid-level managers. Mid-level managers tended to have tremendous influence over their direct reports' behaviors in all aspects of the job, including driving. These managers were required to participate in the same training as their direct reports, but in addition were taught how to observe and document employees' driving skills. Since PPD sales managers were already conducting regular ride-along sessions to observe sales representatives' selling skills, the driver training program taught them how to conduct a safety ride-along at the same time using a driving skills checklist. Managers were then required to submit the checklist to the driver and to the PPD safety department where the results were tracked, summarized, and provided to sales management. Two safety ride-along sessions with each sales representative were required annually, and the managers were encouraged to include the results as part of the annual performance reviews.

The final group targeted was the high-risk drivers. The analyses showed that approximately 80 percent of the vehicle crashes were caused by 20 percent of the drivers. Joe realized that the ability to identify those drivers and provide targeted training and intervention could have a significant impact on the fleet crash rate.

The identification of high-risk drivers involved developing a quantitative risk profile for each driver by assigning points for each crash or moving violation. Risk categories were created that corresponded to different point total thresholds. Then a program of safety training and intervention was designed for each category.

High-risk drivers were identified by assigning points for each driving incident (crash or moving violation) incurred in the previous 36 months. The points associated with each incident reflect its severity as well as Abbott's risk tolerance and safety philosophy (see Exhibit 4). A high risk driver was defined as an individual who had obtained 6 or more points within a 36-month period of time as identified through a Motor Vehicle Record review or equivalent process.

Different levels of intervention were defined for the various degrees of high-risk drivers (see Exhibit 5). For the worst high-risk drivers, an ADTS instructor will accompany the driver during the course of a normal business day, observing the driver's skills and behaviors, identifying problems areas and recommending improvements. Exhibit 6 provides a description of this program. For the lesser offenders, managers could determine the best form of intervention, choosing from options such as driver safety CD-ROMs, videotapes and manuals.

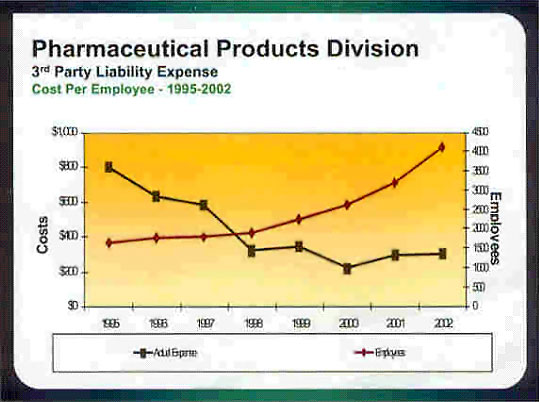

With the expanded program, the division had seen a reduction of nearly 50 percent in third-party liability expenses on a cost per employee basis (see Exhibit 7). Obviously the expenses associated with this kind of program would always be a factor, but Joe thought that it was important to keep the classes to a manageable size to promote interaction in the classroom segment and to allow each driver adequate time to practice new skills during the behind-the-wheel segment. Also, he thought all programs needed to be tailored to the most significant topics, for example, analysis revealed that backing up and rear-end collisions were the two leading causes of crashes. Thus, extra emphasis was placed on these two driving scenarios during the training.

To supplement the training, the safety organization also utilized existing channels within the company such as a newsletter, e-mail, or Intranet to distribute practical, educational reminders about safety to all drivers. They also incorporated driver safety into meetings that fleet drivers were already scheduled to attend, using videotapes or brief seminars to cover targeted topics, and provided programs on topical issues such as changes in cell phone legislation and seasonal issues such as winter driving tips. As of 2003, Abbott required all fleet drivers company-wide to participate in some form of driver safety training every three years, and also dictated that seatbelt use was mandatory in company vehicles at all times.

Exhibit 2 - One-Day Driver Skill Enhancement Program

The ADTS One-Day Driver Skill Enhancement Program is a combination classroom and behind the wheel training. The purpose of this program is not to teach people how to drive; the program is designed to make drivers better. Important information that is vital to safe driving is covered during the classroom portion of the program. Topics include proper scanning techniques, knowing your escape routes, types of collisions and how to avoid them, driving while impaired, passenger restrains and driver attitude and accountability.

The program is designed with the idea that driving is part proper driving attitude and part good driving skills. In the classroom, drivers learn how to stay focused on the task of driving when they are behind the wheel. The driving exercises are intended to improve the driver's abilities and skills. Lessons include techniques to prevent common crashes such as backing and sideswipe collisions, emergency maneuvers to help avoid collisions while maintaining control of the vehicle, and proper methods to react to the mistakes made by other drivers.

The program includes fours hours of classroom instruction and three hours of behind the wheel instruction.

Exhibit 3 - Effectiveness of Behind-the-wheel Training

See text version

Exhibit 4 - Point system for incidents and violations

2 points:

One chargeable accident, Speeding less than 24 mph over speed limit, Seatbelt violation, Failure to stop, Red/yellow light violation, Failure to yield, Improper lane change, Improper turn (including u-turn), Improper passing, Disobedience to traffic device, Failure to dim headlights, One-way street violation, Blocking intersection, Windshield obstruction, Expired operator license, General speed rule violation, Backing violation, and Other violations equivalent to this category.

4 points:

Two chargeable accidents, Speeding 25-35 mph over speed limit, Inattentive driving, Speeding in a school zone, Passing school bus, Emergency vehicle violation, Striking pedestrian, Speeding in a construction zone, Child not restrained in appropriate child safety seat, Negligent driving, and Other violations equivalent to this category.

6 points:

Three chargeable accidents, Speeding greater than 35 mph over speed limit, Reckless driving*, Fleeing/eluding police*, Hit and run*, Driving vehicle under suspension*, Vehicular manslaughter*, Negligent homicide*, Driving without a valid license*, Possession of open alcohol in vehicle*, Driving under the influence*, Driving while intoxicated*, Felony action while operating motor vehicle*, and Other violations equivalent to this category.

* Serious driving infraction that may result in disciplinary action up to and including termination.

Exhibit 5 - Intervention schedule

2 points

Administrative Intervention only, correspondence from District Manager with copy to Regional Manager

4 points

Administrative Intervention: correspondence from District Manager with copy to Regional Manager and face-to-face meeting with District and/or Regional Manager

Training Intervention: Behind-the-Wheel training if not received within previous 36 months, otherwise a videotape and/or workbook with test, a CD-ROM with test, or an on-line program with test.

6 points

Administrative Intervention: correspondence from District Manager with copy to Regional Manager and face-to-face meeting with District and/or Regional Manager, also high-risk driver evaluation sheet placed in employee file

Training Intervention: either Behind-the-Wheel training or One-to-One Behind-the-Wheel session

>6 points

Administrative Intervention: correspondence from District Manager with copy to Regional Manager and face-to-face meeting with District and/or Regional Manager, also One-to-One behind-the-wheel driver evaluation sheet placed in employee file

Training Intervention: One-to-One Behind-the-Wheel session

Exhibit 6 - One-to-One driver training program

The ADTS One-to-One driver training program is designed for drivers who exhibit a need for more intense, personalized training. Drivers with repeat violations or a history of accidents are ideal candidates for this program.

The training is conducted during the course of a normal business day - keeping the driver on the road and productive. As the driver proceeds with his normal business, the instructor makes observations to detect areas that need improvement. While the driver is out of the car on a sales or service call, the instructor makes notes of his or her observations for later discussion. Throughout the day, the instructor provides practical tips and advice whenever possible. At the end of the day, the instructor and driver review the key areas needing improvement and the ways that the driver can begin to address those areas immediately. At completion, the instructor provides a formal report to the driver's manager detailing the key findings and recommendations for improvement.

Exhibit 7 - Third-party liability expense on a cost-per-employee basis

See text version

Fleet Safety at Abbott - Teaching Notes

Many of the characteristics that may make someone a good sales representative may also make them a bad driver, e.g., aggressive, high level of multi-tasking, etc.

Data showed that new hires were a particularly good target group, but to truly affect behavior, an extensive training program of both classroom and driving time was required.

Also, mid-level managers were shown to be a good group to target primarily because as a safety manager, you need to have management commitment to encourage the desired behaviors. Management can influence behavior changes through performance reviews and can also alter behaviors by leading by example. Also, a management commitment is required to provide the financial resources needed for the program.

Key Issues

- To be able to effectively manage a program and improve safety, measurements must include both leading and trailing indicators, and leading indicators should correlate with trailing ones.

In this case, trailing indicators would be based on all the statistics collected by the division after an incident. The Motor Vehicle Record information would support leading indicators to identify the high-risk drivers.

- People are inherently biased when it comes to evaluating risks, and safety managers correctly communicating the risks are important in altering employee behavior and engaging senior management commitment.

Surveys of people and their perceptions of their driving skills generally report that 70 percent of people think that they are above average drivers. People consistently overestimated their skill and underestimate their risk of an accident; education and training is required to overcome these biases. It is often the case that one may be a good driver but that they simply have a few "bad habits".

- 1 This case is based on information provided by Abbott in 2003. This case was prepared as part of an Alliance between Georgetown University's Center for Business and Public Policy, OSHA, and Abbott. Participation in an Alliance does not constitute an endorsement of any specific party or any party's products or services. This case was prepared as the basis for class discussion in the "Business Value of Safety."

- 2 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Traffic Safety Facts Report, 2001.

- 3 Safety + Health, Oct. 2001: 12.

- 4 Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2000 Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, 2001.