Hospitals eTool

Clinical Services » Sonography

Sonography departments use high-frequency sound waves (ultrasound) to create images of organs, tissues, or blood flow inside the body for diagnostic purposes. [See OSHA’s statement regarding its choice of focus points for this hospital area]

Select a common safety and health topic or hazard from the list below to view information related to the topic/hazard.

- Ultrasound scanning

-

Diagnostic medical sonographers and vascular technologists are at increased risk for developing musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). To scan a patient, they often must lean across the person’s body while holding a bulky transducer attached to a heavy cord. If the sonographer is trying to view organs on a patient’s left side, his or her scanning arm can be drawn away as much as 90 degrees. Sonographers also must contort their bodies to reach the keyboard while viewing the changing images on the monitors as they scan. With their workload, sonographers are at risk for MSDs of their necks, shoulders, arms, and wrists. In addition, moving patients onto or from examinations tables, often in an awkward body position, forces sonographers to exert excessive force and increases their risk of injury to the back and shoulders.

Hazards

The most common ergonomic hazards faced by sonographers include:

- Using the same body posture or motions for prolonged periods of time increases the risk of injury to the shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand.

- Lack of adequate height adjustability for examination tables may cause the sonographer to:

- Lean, twist and bend at the waist if the sonographer is too tall for the table height.

- Tilt his or her head forward or to the side if the table is too low.

- Elevate and spread an arm if the table is too high.

- Repeated or prolonged use of extended or elevated reaches to access supplies used for procedures can stress the shoulder and back.

- Awkward posture to view the monitor and use of input devices.

- Tipping the head back or forward places stress on the neck and shoulders.

- Reaching that involves pulling the elbow away from the body can stress the shoulder and back.

- Bending and twisting the torso places stress on the lower back.

- Bending and twisting the forearm and wrist places stress on the hand and elbow.

- Prolonged standing, sitting or holding the arm or neck in a static posture can fatigue the shoulder, leg, neck or hand, as well as create a contact stress on various body parts such as feet, buttocks and the legs.

- Pushing or pulling to position beds, gurneys and wheelchairs prior to transferring patients can require exertion of significant force, especially when dealing with obese patients, carpeted floors or poorly maintained wheels and casters.

- Assuming awkward postures such as bending, twisting or reaching when moving patients from wheelchairs, beds or gurneys to the exam table, especially when combined with the exertion of force, increases the risk of injury to the back, shoulders, and lower and upper extremities.

- Using significant force when lifting obese patients from wheelchairs, beds or gurneys increases the risk of injury to the back and shoulders.

Recognized Controls and Work Practices

- If possible, provide adequate space for maneuvering and orienting people and equipment around the exam table, allowing access from all sides.

- Use examination tables that are height-adjustable to minimize extended reaches, elevated arms and wrist deviation.

- Provide height-adjustable equipment (e.g., monitors, keyboards and beds) so sonographers can frequently change from a seated posture to a standing posture while still maintaining neutral body postures.

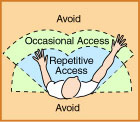

- Place the patient and equipment in a position to allow the sonographer to work, as much as possible, in neutral postures that include: a straight wrist (bent less than 15 degrees), with back straight, elbow close to the body, and head balanced.

- Reposition the patient and equipment to allow the sonographer to alternate between right and left-hand scanning. This provides periods of rest for the hand/arm not used during the scan.

- Keep shoulders relaxed. Do not hunch or raise the shoulders up during the procedure.

- Alternate between sitting and standing positions. When sitting, ensure that feet and back and buttocks are supported.

- Place anti-fatigue mats or pads around the exam area if sonographers must stand for prolonged periods.

- Use mechanical powered transfer devices such as lifts or hoists to move patients, especially those who are obese or non-ambulatory, from wheelchairs, beds, or gurneys.

- When appropriate, use multi-use devices such as chairs that can open up into beds. These allow patients to move from a sitting position to a prone position, without transfer.

- Ensure that additional employees assist in moving and transferring equipment or patients if:

- A mechanical powered device is not available.

- Awkward postures would otherwise result.

- Push force exceeds about 50 pounds.

- Transporting patients and equipment

-

Hazards

Sonographers may be required to move patients or sonography equipment to various areas of the healthcare facility. This may require forceful pushing or pulling of imaging equipment, patient transport equipment (e.g., gurneys, wheelchairs, etc.) over differing floor materials and transitions for a significant distance. In addition, sonographers may be required to assist patients onto and off the examination table when they arrive on any of a variety of transport devices (e.g., gurneys, wheelchairs, etc.). This may require heavy lifting in an awkward body posture. An increase in force exertion may increase the risk of injury to the back, legs and shoulders.

Common ergonomic hazards faced by sonographers while transporting equipment and patients include the following:

- Exerting force in awkward postures, such as bending or reaching, due to handles or push points that are too high or too low.

- Any unexpected, abrupt stoppage or deceleration when moving equipment resulting in the use of excessive force and awkward body postures. This can occur when (for example):

- Wheels are the wrong size for the transitions between flooring types or rooms.

- Wheels are too small to easily pass over gaps between elevator and main floor.

- Wheels (casters) are poorly maintained or are inappropriate for the flooring surface.

- Obstructions placed in the line of travel.

- The floor is damaged.

- Debris is left on the floor.

Recognized Controls and Work Practices

- Use smaller handheld equipment to perform bedside studies, whenever available and appropriate.

- Use mechanical-powered assist devices whenever large or heavy patients or equipment must be moved for long distances (See Figure 1).

- Ensure that equipment has the appropriate wheels (casters) to facilitate safe transport over all flooring and room conditions (See Figures 2, 3, 4).

- Generally, wheels that have a larger diameter, a narrower width and are made of a harder material will traverse gaps and changes in flooring more easily, reducing the necessary push force.

- Swivel casters are recommended when maneuvering in tight locations. Note: Ensure that at least one set of casters is lockable to provide improved inline steering.

- Ensure that all equipment is maintained according to established schedules and that all employees understand the procedure for reporting damaged equipment.

- Ensure that the controls for equipment are easily accessible without bending or reaching. Applicable controls may include controls that allow selection between two-wheel, four-wheel and braked positions and controls for central locking (which provides greater stability to the equipment).

- Place handles on the swivel caster end of equipment to ensure that sonographers push or pull from this end.

- Ensure that floors are clean and free of debris that may cause the wheels to get stuck while in motion.

- Ensure that aisles are kept open and free of extraneous items such as gurneys, wheelchairs or other carts.

- Ensure that employees are aware of the procedures to report damage to flooring and walkways.

- Train sonographers to use correct body mechanics when moving patients, wheelchairs, beds, stretchers and ultrasound equipment (See Figures 5 and 6), including training in the following practices:

- Push instead of pull. Lean slightly into the load to let your body weight assist with force exertion.

- Push at about chest height.

- Push smoothly and slowly to start.

- Do not bend or twist while exerting force.

- Keep wrists straight.

- Keep elbows close to the body.

- Use an air mattress or sliding sheet for lateral patient transfers between the gurney and examination table.

Additional Information:

- Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for Our Caregivers – Safe Patient Handling OSHA.

- Safe Patient Handling. OSHA Safety and Health Topics page.

- Safe Patient Handling: Preventing Musculoskeletal Disorders in Nursing Homes. OSHA Publication 3708, (February 2014).

- Inspection Guidance for Inpatient Healthcare Settings. (June 25, 2015). OSHA memorandum establishing guidance for inspections conducted in inpatient healthcare settings.

- Also see Hospital-wide Hazards - Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders.

- Industry Standards for the Prevention of Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Sonography. Society of Diagnostic Medical Sonography (SDMS), (May, 2003).

- Preventing Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Sonography. US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Publication No. 2006-148, (September, 2006).

Hazards

Employees who use a computer intensively (e.g. for data entry) are at increased risk for developing musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) of the hand/arm, shoulder, neck, and back. The risks of developing MSDs and other ergonomics-related concerns associated with using computer workstations are especially heightened for sonographers because of the following:

- Repeated reaching to the keyboard while performing ultrasound exams can stress the upper arm and shoulder.

- Repeated use of awkward postures due to inappropriately placed monitors, including:

- Repeated or prolonged looking to the side to view monitors.

- Repeated or prolonged tilting of the head up or down to view monitors that are too high or too low. This is especially a problem for sonographers who wear bifocals.

- Leaning forward to view distance monitors or monitors with images that are unclear due to poor resolution or excessive ambient lighting.

- Eye strain, blurred vision, double vision, dry eyes and headache resulting from prolonged concentration to view images that are unclear or washed out on the monitor.

- Lighting that does not include dimmer switches or controls makes monitors difficult to read. This may lead to eye strain and back and neck discomfort as sonographers lean forward to detect items on the screen.

Recognized Controls and Work Practices

Look at the workstation layout:

- Arrange materials and supplies in front of the sonographer’s body so that they can be easily reached with the elbows in close to the torso.

- Provide adjustable, supportive padded chairs that support the forearms, legs, and low back. The proper height of the arm rests allows the elbows to hang normally at the side of the body.

- Arrange monitor so that the most commonly viewed area is slightly below (about 20 degrees) horizontal eye level and can be seen without looking up, or leaning forward.

- When possible, use a fully adjustable monitor on a monitor arm that is detached from the main console and can be easily positioned for both sitting and standing postures and for a variety of procedures. The following can help maintain a correct body posture:

- Place the monitor directly in front of the sonographer to minimize looking to the side.

- Place the top of the monitor at about eye height with the viewing area slightly below eye height.

- The monitor may need to be adjusted downward for bifocal wearers.

- Place the monitor about 18 to 30 inches in front of the sonographer.

- Generally, flat screen monitors are lighter and easier to adjust to varying positions for a variety of procedures.

- Limit awkward positions when possible, (e.g., provide headsets for employees to use when answering phones).

- Use a keyboard that includes an adjustable mouse support that can be easily reached from a keying position. Employees need to keep wrists straight while typing and use wrist pads to rest on when not typing. Consider use of a touchscreen.

- Add dimmer switches to allow reduced room lighting to make the monitors easier to read.

Repetitive Motions during hand-intensive tasks: Performing hand-intensive tasks (such as data entry, word processing) with a bent wrist creates considerable stress on the tendons and their sheaths as they are bent across the harder bones and ligaments that make up the outside structure of the wrist.

- As the fingers are activated, the tendon slides through the sheath and over the hard parts of the bent wrist, pinching the sheath between the tendon and these hard entities.

- Repetitive finger activations in these postures can create wear and tear on the tendon and the sheath.

- Prolonged forceful finger exertions in these postures can stretch and fray the tendon and create contact trauma to the sheath.

This wear and tear, fraying, or contact trauma can create irritation and swelling that may lead to tendonitis, tenosynovitis, and potentially carpal tunnel syndrome.

Additional Information

- For more information, see OSHA's Computer Workstations eTool.

- Industry Standards for the Prevention of Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Sonography. Society of Diagnostic Medical Sonography (SDMS), (May 2003).

- Preventing Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Sonography. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Publication No. 2006-148, (September 2006).

Workers in hospital settings may be exposed to a variety of common and emerging infectious disease hazards, particularly if proper infection prevention and control measures are not implemented in the workplace. Examples of infectious disease hazards include seasonal and pandemic influenza; norovirus; Ebola; Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), tuberculosis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA), and other potentially drug-resistant organisms.

Infectious diseases are caused by agents that are transmissible through one or more different routes, including the contact, droplet, airborne, and bloodborne routes. The transmission of infectious agents through the bloodborne route—a specific subset of contact transmission—is defined in the Bloodborne Pathogens (BBP) standard, 29 CFR 1910.1030 (See the Bloodborne Pathogens section below).

An effective infection control program normally relies upon a multi-layered and overlapping strategy of engineering, administrative and work practice controls, and PPE. It is OSHA's intent in this eTool to highlight some – not all – of the controls that would be necessary to the development and implementation of an effective program. Implementing the controls highlighted here alone will not typically protect workers from infection hazards.

Follow standard and transmission-based precautions to prevent worker infections (see also the OSHA page: Worker protections against occupational exposure to infectious diseases). Early identification and isolation of sources of infectious agents (including sick patients), proper hand hygiene, worker training, effective engineering and administrative controls, safer work practices, and appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), among other controls, help reduce the risk of transmission of infectious agents to workers.

Employers must comply with the BBP standard to the extent that there is "occupational exposure" (i.e., to the extent employers should reasonably anticipate contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials (OPIM) that may result from the performance of duties). Employers must also comply with the PPE Standard, 29 CFR 1910 Subpart I, and the OSH Act's General Duty Clause, 29 U.S.C. 654(a)(1), to protect their workers from infectious disease hazards. The General Duty Clause requires each employer to "furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees."

OSHA provides agent-specific guidance for a variety of pathogens that workers in hospital settings may encounter. See OSHA's Safety and Health Topics Pages for Biological Agents and Bloodborne Pathogens and Needlestick Prevention for additional information.

In this module, OSHA provides additional guidance specifically for bloodborne pathogens.

- Bloodborne pathogens (BBP)

-

Bloodborne pathogens are pathogenic microorganisms present in human blood that can cause disease in humans. These pathogens include, but are not limited to, Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (e.g. Ebola). [29 CFR 1910.1030(b)]

Hazards

Exposure of staff to blood and other potentially infectious material (OPIM) (e.g., excreta, vomit, sputum) during the sonography process.

Requirements under OSHA's Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, 29 CFR 1910.1030

The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard requires precautions when there is occupational exposure to blood or OPIM (as defined by the standard). Under the standard, OPIM means (1) the following human body fluids: semen, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid, pleural fluid, pericardial fluid, peritoneal fluid, amniotic fluid, saliva in dental procedures, any body fluid that is visibly contaminated with blood, and all body fluids in situations where it is difficult or impossible to differentiate between body fluids; (2) any unfixed tissue or organ (other than intact skin) from a human (living or dead); and (3) HIV-containing cell or tissue cultures, organ cultures, and HIV- or HBV-containing culture medium or other solutions; and blood, organs, or other tissues from experimental animals infected with HIV or HBV.

OSHA requires employers to ensure that the biosafety officer or other responsible person conducts an exposure determination to determine the exposure of workers to blood or OPIM throughout the hospital setting. [29 CFR 1910.1030(c)(2)(i)].

For more information, see Hospital-wide Hazards - Bloodborne Pathogens.